Meng and Hugh are both mentors at the Founder Institue Singapore. Last night was a veritable Penn reunion: Adeo Ressi (Penn ’94 dropout), Scott Rafer (Penn ’90 and JFDI mentor), and Meng (Penn ’96 and JFDI Frog) spoke on the subject of Startup Research.

Meng and Hugh are both mentors at the Founder Institue Singapore. Last night was a veritable Penn reunion: Adeo Ressi (Penn ’94 dropout), Scott Rafer (Penn ’90 and JFDI mentor), and Meng (Penn ’96 and JFDI Frog) spoke on the subject of Startup Research.

Meng would like to offer the following highlights from his talk before he forgets them:

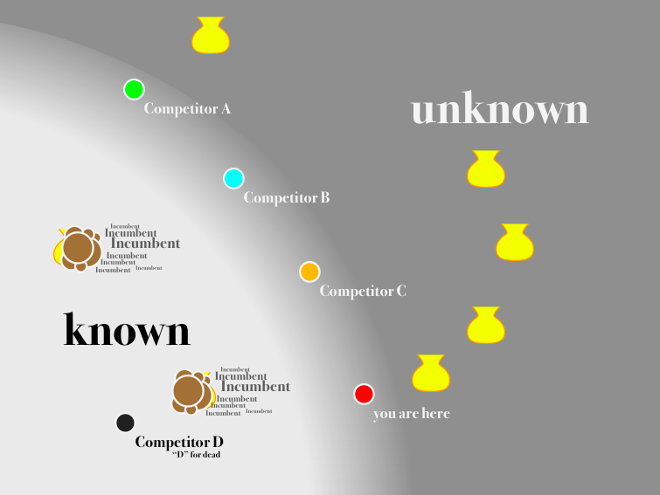

Innovation can be considered a search in multidimensional space for loci of business value at the frontier between the known and the unknown.

Within known space, loci of business value are well understood: McDonald’s is one enduring combination of variables, located at an attractor around which Burger King and Jollibee also orbit. Same with high-speed broadband, cell phone service, business card printing, and the netbook.

Beyond known space lie fountains of value which remain unexplored. Life extension and space travel are just coming into view.

Between those zones, within the frontier, one finds a frenzied search for winning combinations of product, business model, distribution channel, and all those other factors in the space of possible business configurations. This should be familiar to scientists: it is merely a search for local maxima within a multivariate space. Scientists don’t have to be afraid of business. They already have statistical tools and empirical methodologies that leave the Excel monkeys in the dust. In this view, Lean Startup methodology is just a template for scientific discovery of business value.

Innovation is nothing more than the (often exhaustive and often exhaustingly brute force) search for previously inaccessible loci of value made newly reachable by historical forces such as progress in technology, shifts in the environment, and demographic inevitabilities. Individual innovators are like ants, endlessly crawling down the beach as the tide goes out.

Entrepreneurial innovation – where you have to start a company to test a hypothesis – is often necessary because large companies like to nest; having discovered an oasis of value they defend it to the death, rarely sending out scouting parties to the frontier. It’s dangerous out there. But it’s even more dangerous to stay high up on the beach. The tide endlessly recedes, and if you don’t stay close to the water you eventually bake to death in the sun. Clayton Christiansen talks about the fate that befalls incumbents who ignore disruptive innovations.

The search for new founts of value is more efficient when informed by a new paradigm, philosophy, or aesthetic. Scott Rafer said that VCs are always happy to take meetings because they’re looking for some founder who’s got a new model of market segmentation that they haven’t seen before. Looking at a market or value proposition in a new way is what allows businesses to invent the SUV, or Vitamin Water, or Bacon Salt.

Entrepreneurs who are not guided by an underlying philosophy have no choice but to brute-force hill-climb, one pivot after another in a drunkard’s walk. That’s inefficient. Better to use a new paradigm to inform your search. It pays to be smart and well-educated. Just as a knowledge of Keplerian orbital theory tells astronomers where to point their telescopes, a sophisticated understanding of human psychology and market behaviour allows entrepreneurs to adjust the levers and navigate quickly to new points in multivariate space. Charlie Munger’s mental models are like bases in perfumery. You can combine them sexually to create new ideas; as Fredrik Härén says, new ideas are nothing but two existing ideas put together in a new way.

But the creative impulse behind the search – that drives a Christopher Columbus to set sail for the New World – is always the same. It is the purest expression of design thinking. Adeo put it best: “This is broken and needs to be fixed.”

If you’ve ever said that about something – a piece of equipment, a drawing, a piece of writing, a political situation, a business process, a computer program – you just might be unreasonable enough to cause progress.