Alongside our community and the investment we put into our bootcamp startups, teaching is important for JFDI.Asia too. Our growing relationship with Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) is a two-way exchange of ideas: the fresh way that undergraduate students interpret methods like Lean Startup makes us think again about issues like what actually is a minimum viable prototype, writes Hugh Mason.

Alongside our community and the investment we put into our bootcamp startups, teaching is important for JFDI.Asia too. Our growing relationship with Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) is a two-way exchange of ideas: the fresh way that undergraduate students interpret methods like Lean Startup makes us think again about issues like what actually is a minimum viable prototype, writes Hugh Mason.

The classic advice from gurus of Lean Startup is to get out of the building with a Minimum Viable Prototype and go talk with customers. There are several reasons why many of us find this kind of Customer Discovery Process hard.

First up, walking up to strangers and asking for an in-depth conversation doesn’t come naturally to everyone. Then, a little voice inside asks “What do I actually say?”, followed quickly by “Err… what if they don’t like my idea?”

If you can hack code or do design, it’s tempting to stick in your comfort zone and find every reason not to talk with people. Given half a chance, many of us prefer to sit inside, perfecting our ideas, hoping that their brilliance will speak for itself.

It’s very natural and it won’t work. In the words of Linked-In founder Reid Hoffman:

If you’ve released it and you’re not embarrassed by it, you’ve released too late

I’d go further. I would say that that, unless you are not embarrassed by a prototype, you won’t ask the right questions. Your mindset will be to look for validation, which is not at all the point of ‘customer discovery’.

You don’t want a pat on the head. You want customers to tell you what needs fixing so they clamour to give you money.

Which is why SUTD gives students taking its entrepreneurial Start Something course plenty of practice. Alongside traditional design and engineering they learn to create quick-and-dirty prototypes to prompt insightful conversations.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=STeTOHXkFPQ

What constitutes ‘viable’ for a prototype depends on the stage of development for a business. If all you want to do is to engage customers in a conversation to begin to understand the problems and opportunities they see, then something that gets a laugh because it’s so crap – like a paper or cardboard mockup – is absolutely fine.

A really low-tech prototype, like some hand-drawn bits of paper held over the screen of a handphone, has the benefit that everyone can see you are not pretending to have a finished product.

A really low-tech prototype, like some hand-drawn bits of paper held over the screen of a handphone, has the benefit that everyone can see you are not pretending to have a finished product.

By making it blindingly obvious that you are just sketching out ideas, you invite the person you’re talking with to project what they want onto your “prototype”. You give them permission to start disclosing what they actually want and you flatter them by asking for their advice. It’s all about setting the right ‘frame’ around the conversation.

I’ll write soon on how some ideas from psychology can help to steer those conversations soon.

In the meantime, if you’re feeling like you’re blocked from exploring a business idea, is it possible that you have become too focused on one aspect of it and another could be an easier place start? Maybe a prototype for that would be much easier to conceive and execute.

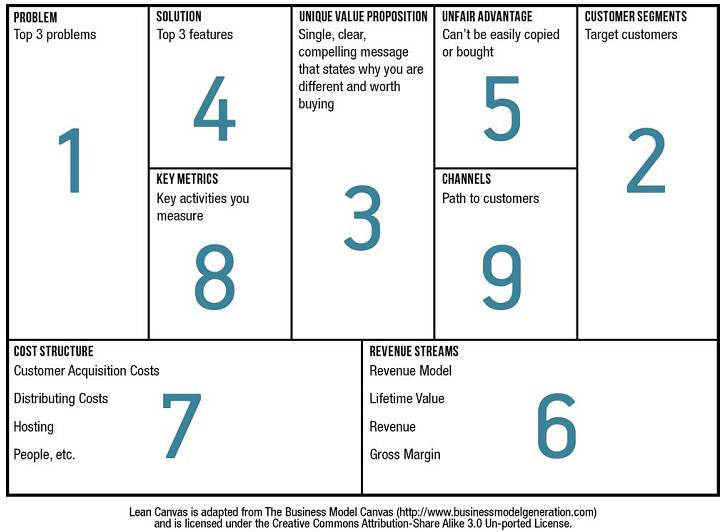

I find it helps immensely to think of a business holistically from the get-go. At JFDI.Asia we use tools like the Lean Canvas to focus our start-ups on thinking this way and to make it easy to share that thinking with mentors. Eventually, all the boxes below need to be filled and the words in them tested, requiring many iterations of the prototype:

The numbers on this canvas suggest a sensible order to complete the boxes, but there is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem around the first two. If you don’t know who your customers are, how can you identify their problems? Like so much in Lean Innovation, the solution lies in iteration. In practice, you might start somewhere else.

For example, you might see an opportunity to reach a group of people that haven’t been easy to contact. You’ve spotted a Channel – box 9. So the very first prototype you create might be a message that tests if the channel works – is anyone listening?

Only when you’ve proved that you can make direct contact with the group of people at the end of such a channel would it make sense to start identifying which specific sub-groups are potential customers (box 2) and what problems they want solving (box 1).

The one place on the canvas that we dissuade anyone from starting is with a solution that’s looking for a problem, because doing that will tend to bias you towards selling the solution instead of listening to customers. Unfortunately it’s also the place most people want to start when they think they have an idea.

Bringing it all back to practical actions – if you’re holding off on exposing an idea to the world, and prototyping seems like a barrier, you could ask yourself:

- What’s stopping me going out and talking with potential customers right now?

- If I don’t have a fully-formed idea, could I ask potential customers that interest me about problems they have or opportunities they see? Ask first, speak later … if they don’t see the world the same way as me, why not?

- Do I need to code anything? Could I make something out of paper and cardboard to start a discussion?

- Maybe my MVP is a phrase or two sentences, initially. Can I write the idea on a post-it, learn it and ask people about it? When I do, are they intrigued, or do their eyes glaze over?

- Would a single webpage somewhere like launchrock get me started?

- If I really need to visualize this idea, can I mock it up in an image editor, or something like Balsamiq?

- Can I post the idea somewhere like Open Frog? If I am afraid of it being copied, because that’s incredibly easy, is the idea actually worth doing?

I was inspired visiting the students at SUTD this weekend. Some of them are only just learning to code and design. That’s why they are studying and actually it’s an asset that coding and design is not yet a comfort zone. It forced them to use imagination to create prototypes. In doing that, they taught me something.