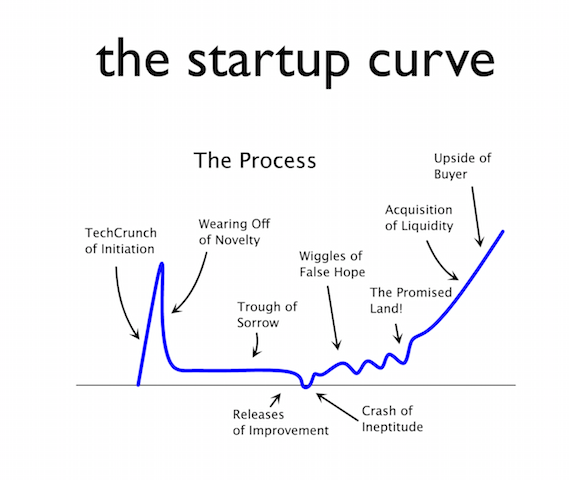

From Paul Graham’s “Trough Of Sorrow” to the joy of winning a first customer then stories of chronic depression… let’s face it… doing a startup is an emotional rollercoaster. So what can Pixar’s blockbuster movie Inside Out and new research teach about the turmoil in founders’ heads? asks Hugh Mason

From Paul Graham’s “Trough Of Sorrow” to the joy of winning a first customer then stories of chronic depression… let’s face it… doing a startup is an emotional rollercoaster. So what can Pixar’s blockbuster movie Inside Out and new research teach about the turmoil in founders’ heads? asks Hugh Mason

Those of you who were at JFDIs Open House last Friday will have heard a brave founder share her personal experience of mental health issues and the great way that motivated her to launch a startup called Psychkick with friends. Her honesty in a country where this subject is still taboo prompted me

to share that I just finished 8 years of psychotherapy.

I talk about it openly because it’s been such a benefit for me personally and professionally and because so many others face challenges with anxiety, stress, depression and the like. The research I have read says that 1 in 7 of us will need residential care for a mental health issue at some time in our lives and 1 in 4 families are affected. Yet we don’t talk about it, so I started a meetup group with a friend that has grown to over 2,000 members here in Singapore.

Another friend in our community, investor Chow Yen-Lu, started Wholetree Foundation with his wife Yee Ling in memory of their son who, tragically, they lost following his battle with mental health issues. Hats off also to James Chan, who writes openly about the more everyday challenges he faces trying to do the right things as a Dad while also balancing the stretch of his business Silicon Straits.

I think it’s vital that our community talks about the challenges openly because, as entrepreneurs and innovators, we have chosen a working lifestyle that is a little bit stressful sometimes, to say the least. It comes with the job. We need help to make sense of that, just like an athlete needs help with their diet. Stress and anxiety are part of the deal for entrepreneurs and the quicker we can start talking openly about that with each other, the quicker we can acknowledge it, take a deep breath, and Just Frogging Do It anyway.

The final prompt for writing about this now is that we’ve reached the time in our current 100 day accelerator program when FUD (Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt) usually sets in. I see it clearly in the faces of our startup founders. Just a few weeks ago, everyone arrived with a clear picture of what they were doing. Focusing on it day in day out and having mentors pull it apart and talking with those idiot customers who just don’t get it has started to wear them down. It’s

A friend called Christie Scollon is an Associate Dean and Professor of Psychology at Singapore Management University. She’s helped me understand why this trough and in particular pivoting a business is so very uncomfortable. Her students put together a 5 minute Guide to Overcoming the Trough of Sorrowspecially for stressed startup founders.

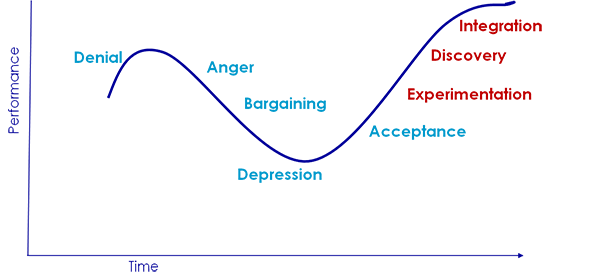

This process might take years, if someone is grieving about losing a life-partner. Or it might take minutes or hours if they have lost their wallet.

Here’s one representation of the ‘change curve’ that might just explain why so many founders fall out with each other as they struggle to adjust after the collective delusion that brought them together:

The thing I find most interesting about this is that the first stage is ‘denial’. Perhaps every startup venture requires the team to ‘suspend their disbelief’ and in doing so set themselves up for an emotional fall. In other words there really might be some truth in the old stereotype that you have to be slightly nuts to start a business. I like to imagine, if that’s true, that this quirk in our makeup had, and still has, an evolutionary advantage for our species: if it weren’t for that entrepreneurial urge, we might all still be huddled in caves afraid of what might be outside, or lurking on the bottom of the sea waiting for food to fall in our mouths like crabs. But that’s just speculation on my part.

What is certain is that entrepreneurs face loss every day. Clients and Investors say no. Business models and staff hires don’t work out. That stuff is external and kind of expected, like the physical pain of running a marathon. Much harder is when I have to let go of something inside me that feels like part of me—an idea—my vision of what I want to create or my mental model about how the world works. Then there is a profound sense of loss.

Meng, my sage co-founder, likes to tell the legendary story of an old professor, sitting at the back of a lecture theatre as a young researcher shows new evidence that the old professor’s theories—the life’s work on which he built his reputation—are in fact wrong. In the story, the old professor walks up to the young man and shakes his hand, thanking him for revealing the truth.

Most of us don’t have that fortitude. So we play a psychological game with ourselves, avoiding testing the assumptions that might make our idea fail. We find reasons why the hard-hitting advice from a mentor might not be true. We hold onto team members who are failing until they drag us all down because it feels shameful to admit that the fit is not right. And especially in the startup stage we hold off making pivots until it’s too late and we’ve run out of cash. It takes superhuman mindfulness to let go of our cherished ideas because we know in our hearts that, once we let go, it will feel like falling. Hard.

Our experience at JFDI is that it’s a lot easier to deal with this feeling and let go anyway if you are in a group that trusts each other and can watch out for each other. That’s why we have cohorts and why we try to encourage all members of all teams to hang out together as much as they can. Not only can we help each other by talking about how we feel but we can help others avoid chasing down dead ends too. A good starting point is to become mindful of exactly how you are feeling, which is why every JFDI operations meeting starts with us going round the room asking people to choose one word that describes their mood.

I personally find that understanding the psychology of this helps me to cope. If you have seen the movie ‘Inside Out’, you have watched a carefully researched and remarkably accurate representation of how our emotions work, played out in animated characters who drive the people in the story. Only one of the basic emotions gets to drive each person at any particular moment. That’s true in real life and incredibly helpful because, even when our heads are buzzing with thoughts, our hearts will only ever feel one emotion at a time (even if the feeling flips quickly back and forth between two emotions like nervousness and excitement before you go on stage.)

A good starting point is to become mindful of exactly how you are feeling.

So even if I don’t know exactly what I think about a situation, I can almost always figure out how I feel about it, if I stop for a moment and just listen to myself. Shaun Martin, a cognitive scientist who often comes to our Friday Open House, says that is important because our emotions evolved over 100,000+ years to help us survive long before we had language and the kind of analytic thought we so treasure today. We can feel much faster than we can think and often that can be a life-saver.

If you want literal proof that this is the case, not just ‘namby-pamby psychobabble’, watch one of Shaun’s favourite videos:

The man walking is clinically blind because the centres in his brain that form the image of the world that sighted people enjoy are no longer working. He cannot ‘see’ a hand if you hold it in front of his face. Yet he can navigate a room full of obstacles without thinking. He says he does it because he can feel where to go. The explanation is that our brain interprets the signals from our optic nerves in many ways and the one that dominates our consciousness – an image of the world for those of us who are sighted – is only one of them. At a much deeper level the ‘reptile brain’ at the top of our spinal cords can influence our movements directly without us needing to think.

Animals that don’t have our level of cognition are still able to perform extraordinarily effectively in the wild because their brains have evolved to see patterns and pattern-recognition is one of the key skills for entrepreneurs. So if you feel something… take note of it.

The feeling may be helpful or unhelpful but it is there for a reason. Ignore it and, at best, you may be throwing away one of the best tools we have to deal with uncertainty. At worst you may bottle up frustration for the future.

I have come to believe that our emotions are there to remind us that something we are experiencing now is like a pattern we have seen before. The pattern could be something that happened in our childhood that is now irrelevant, unhelpful baggage that holds us back. Or it could be a very helpful signal. So it’s important that we can stand back from our emotions and make sense of what they are signalling.

If you’ve seen the classic Star Trek episodes this always plays out in the drama between Kirk and Spock. Whenever the Starship Enterprise and its crew face a difficult situation, Spock’s logic helps but it’s Kirk’s intuition that almost always brings victory. You face the same situation when two mentors give you conflicting opinions, or you have to deal with incomplete data.

To give one example: I encouraged one of the startup teams I met with yesterday on our Accelerate program to burn through the money that JFDI is investing as quickly as possible. I said that because I think he has a model that is fundamentally working and that he will get more traction and a better valuation if he just goes for it and ramps things up to the max. We agreed that no kittens will die if something breaks and, if something does break, it should be easily fixable.

I felt this was a really important discussion because the entrepreneur concerned seemed to me to be holding himself back. We didn’t have time to discuss why, but I have a hunch it might be because he’s worried that, if the business doesn’t work and he’s burned the cash, either he won’t raise more money or that investors will be angry with him. He’s relying on a pattern about conserving cash which is great advice in many situations in life. But here, the opposite is true.

If the entreprenuer burns through the cash we have given him intelligently, showing that there is an awesome business to be built, then asks ‘please can I have some more money?’ the answer will be yes. And if he ends up showing it doesn’t work then investors will be glad because now they know they can stop wasting cash. They mentally wrote off the investment already, as every early-stage investor must do the minute they sign a cheque. No kittens will die if the business doesn’t work out.

The only way he can fail and be blamed is for being too cautious because then he would not complete his mission – to explore the biggest risks in the business model as quickly as he can. Staying mindful of how we feel as well as think can often help us unblock the path ahead.

The book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” talks about the difference between emotional gut feelings and the more logical system. Author points out some cognitive biases (alas not the moral certitude that many entreoreneurs have to cross valley of death) but the pattern recognition can be acquired through years of discipline (aka communities of practice). He cites case of firechief who ordered retreat b4 floor collapsed, only afterwards rationalise ear felt too hot but too quiet do real fire underneath. Mindfullness helps feedback loop to cultivate the gut & supported by data (humans notoriously bad at statistical inferences). This foundation training is just start of entrepreneur to pick partners, engage employees or give customer credit.

Thank you Lawrence! That’s a good additional resource to those who found this article a starting point.