The JFDI-Innov8 2012 Bootcamp was incredibly intense. We were strangers when we started but got to know each other very well. My family got involved, testing prototype games from several teams, writes Hugh Mason.

The JFDI-Innov8 2012 Bootcamp was incredibly intense. We were strangers when we started but got to know each other very well. My family got involved, testing prototype games from several teams, writes Hugh Mason.

In this post I want to share some of the background thinking and, in particular, why we’re not precious about ideas. Truth is, we would be quite happy to recruit teams into JFDI who have no ideas at all.

We’re much more interested in people who share our interest in what users and customers think. It’s customer needs, not our ideas, that mark the starting and end points of our journey.

Creativity versus Innovation

There are many definitions of creativity so I’ll throw mine into the mix: Creativity is the skill you need to invent things and come up with new ideas.

Innovation is different. It’s all the things that have to happen when an idea gets put into practice for the first time.

Innovation might involve creating something new but it could just as well be about taking a good idea from one place and introducing it somewhere else. That’s what we did with JFDI itself. The ideas behind our bootcamp were pioneered in the US and we were just the first to bring them to South East Asia. That was our innovation.

But let’s go back to creativity for a moment. I’ve learned a lot about it from my son, Max.

Max had his 6th birthday on Sunday and he’s just discovered jokes. This is one of his favourites:

What do you get if you cross a cow with an earthquake?

A milkshake!

Ok it’s not the funniest joke in the world. I share it here because, in reading it, we go through something similar to having an idea. It happens in three stages.

- First we read about two things that don’t really belong together in the set-up.

- Then we feel kind of tense and puzzled as our brains try to make sense of how those two things belong together.

- Finally there’s an emotional sense of relief when we discover how the two things fit together in the payoff.

We laugh, just like our ape ancestors have been doing for millions of years, to signal to others around us that everything’s OK. Something’s changed, but there’s no threat. Chimps may not crack one liners but they do laugh, much like us, to reassure each other.

Having an idea has a lot in common with humour. Both are about bringing things together that don’t, at first, look like they belong. The logical part of our heads – the left brain – struggles to work out how they fit. Psychologists call that cognitive dissonance – like two notes in a piece of music that don’t seem to make a harmony. It’s the right brain that makes the music and finds a connection, if you let it.

When it comes to ideas, even the most logical of great scientists relies on a completely different system – one that’s much more about feeling than thinking.

When it comes to ideas, even the most logical of great scientists relies on a completely different system – one that’s much more about feeling than thinking.

About 60 years ago, Arthur Koestler wrote an elaborate theory about this in his book the Act of Creation. It isn’t a complete explanation of creativity, or the only one out there, but for folk like me who have spent a working life in the ideas business it still has a ring of truth about it.

Koestler said that the moment we invent something, there’s a spark. It’s as if two things from different parts of our experience weld together, making something whole and new.

If we don’t feel that spark, we feel uncomfortable. It’s dissatisfying, like a piece of music that just stops without a proper ending. But if we can live with the tension until the cognitive dissonance resolves, we feel the emotional release of a flash of insight.

The spark of two ideas welding together is what creative people are hooked on. It’s addictive, infectious and its brilliance is the reason we value the special people who come up with great ideas so highly.

But what if we are all born able to do this?

Malcolm Gladwell wrote about research that shows you need to put in perhaps 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert at more or less anything. Creativity is just the same. It gets better the more we practice. If you want to give it a go, one tip seems to be to stop thinking and start doing. Give yourself permission to play.

Again I think of my son Max. He loves lego. When he’s making something I’ll ask: “What’s that you’re making?” Almost always he will reply – “I don’t know yet. I’ll tell you when it’s finished.”

Again I think of my son Max. He loves lego. When he’s making something I’ll ask: “What’s that you’re making?” Almost always he will reply – “I don’t know yet. I’ll tell you when it’s finished.”

The lego in Max’ hands might become a rocket or it might become a dinosaur. He hasn’t decided yet. This kind of play is about doing, not thinking. Again the psychologists have a word for it: they call itexperiential learning.

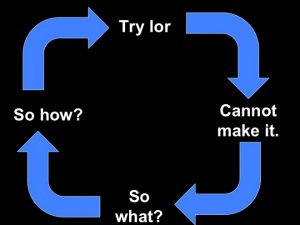

It’s the opposite of what we are taught at business school (identify the goal, figure out the best way to do it, then execute your plan). Max does it back to front: he tries it first, then works out what he’s doing later.

Psychologist David Kolb wrote about this in the early 1980s, building on studies of child development stretching back over a century. Kolb realized that creativity is closely linked to invention through something he called the learning cycle. My co-founder Meng Wong kindly came up with a Singlish version of it.

Creativity guru Hilary Austen haswritten about how all creative people use this experiential knowledge to make sense of the world. But they also get a sense of direction from their culture (directional knowledge) and the intellectual maps they learn (conceptutal knowledge).

Creativity guru Hilary Austen haswritten about how all creative people use this experiential knowledge to make sense of the world. But they also get a sense of direction from their culture (directional knowledge) and the intellectual maps they learn (conceptutal knowledge).

So, when a ceramic artist picks up a lump of clay, she knows from experience that “If it feels like this, when I fire it in the kiln, it will come out like that”. If she follows a religion that has a taboo around representations of the human form, she takes a steer fromdirectional knowledge. And if she gives a lecture about art history, mentioningpostmodernism, surrealism or the pre-raphaelites, she is sharing conceptualknowledge.

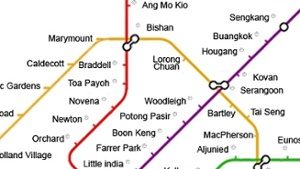

For a long time, conceptual knowledge like that was prioritized in Singapore’s education system. It’s like learning how the MRT is laid out by looking at a symbolic map – a great way to get your head around the big picture. As a passenger an underground train, you don’t need to know all the twists and turns of the tunnels. You just need to know where to get on and off.

For a long time, conceptual knowledge like that was prioritized in Singapore’s education system. It’s like learning how the MRT is laid out by looking at a symbolic map – a great way to get your head around the big picture. As a passenger an underground train, you don’t need to know all the twists and turns of the tunnels. You just need to know where to get on and off.

But that’s not true for a lot of things in real life. You can’t learn to walk conceptually. Thinking hard won’t help you to ride a bicycle, be a good parent/lover or to start a business. The only way to master these things is to have a go, make some mistakes, fall over and get up again.

We have to play at a lot of things in life and that’s particularly true for creativity. It’s why families need to be supportive places for young people to make their mistakes safely. Every loving parent and every professional creative knows this. So do all great entrepreneurs and technical innovators.

This is the second of a three-part series looking at the links between creativity and lean innovation. In the final part I’ll explore the link between creativity and the special way that successful entrepreneurs work.