Back in 1877, Thomas Edison liked to chill out with his iPod, just as we do today. The phonograph was just one of 2,332 inventions that he patented in an extraordinary lifetime. The industries he created, from electric power to recorded music, generated immense wealth. His working style also pioneered many of the practices we now bundle up and call Lean Innovation.

Edison still ranks among the top five most prolific inventors in history. Yet, in his own words:

I never did a day’s work in my life, it was all fun.

Incandescent light was an early innovation. A lightbulb rapidly became the cartoonist’s shorthand for a bright idea – the spark of creativity – which is ironic because the real one didn’t come in a flash at all. Quite the opposite, in fact. Edison tried 3,000 different ways to make a lightbulb before he found a design that was practical. He didn’t see any of the others as failures – they were just necessary steps that gave him feedback to help find the breakthrough.

was an early innovation. A lightbulb rapidly became the cartoonist’s shorthand for a bright idea – the spark of creativity – which is ironic because the real one didn’t come in a flash at all. Quite the opposite, in fact. Edison tried 3,000 different ways to make a lightbulb before he found a design that was practical. He didn’t see any of the others as failures – they were just necessary steps that gave him feedback to help find the breakthrough.

Another of Edison’s inventions was the industrial research lab. Today’s research institutes, like Singapore’s A*Star, descend directly from Edison’s lab at Menlo Park, California.

Even though the technology inside has changed out of all recognition, curiously, the architecture of many modern research centres still echoes the mystique that Edison created around invention during his lifetime. For example, he encouraged rumours that he never slept and ate only apple pie and ice-cream. To this day, the myth that invention has to be done by strange people in strange places lives on. This tent is the Schlumberger research centre in the UK – it’s a tent in the middle of a field.

Another of Edison’s quotes is about how he built valuable ideas:

I find out what the world needs. Then, I go ahead and invent it.

Today’s gurus of Lean Innovation, like Steve Blank, call that Customer Discovery.

What people want is, by definition, what’s valuable. Yet we want different things in different contexts. So how?

I’ve mentored about 350 “ideas businesses” over the last 15 years and most of the time, most people seem to want one or two out of three things:

- Some people want to do great work. They want to create cultural value. They might want to contribute a beautiful work of art, or a beautiful theory of neuroscience, but it’s the beauty of it that turns them on.

- Some people want to make the world a better place. They want to create social value. They might want to change the world (looking outwards) or simply to create a fabulous workplace where people like them can feel fulfilled (looking inwards).

- Others want to make money. They want to create economic value. (I find that folk who only want to do this usually don’t succeed)

These three aren’t necessarily exclusive. Yet there is a tension between them, because doing just one of them brilliantly is hard. I’ve found that confusion between those goals is the number one reason why many ideas businesses fail to move forward. Anyone can have ideas (creativity) but a whole load of other things have to come together for an idea to become useful reality (innovation). Once again, Edison had it nailed:

None of my inventions came by accident. I see a worthwhile need to be met and I make trial after trial until it comes. What it boils down to is one per cent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration.

It’s not as if creativity on the spur of the moment is always a good idea anyway. For example, most of us would prefer a surgeon to have done some planning before they operate on us. OK they need to be creative when they patch us up after a car-crash but it would be nice to know they aren’t totally making it up as they go along.

It’s not as if creativity on the spur of the moment is always a good idea anyway. For example, most of us would prefer a surgeon to have done some planning before they operate on us. OK they need to be creative when they patch us up after a car-crash but it would be nice to know they aren’t totally making it up as they go along.

Then again, we have to give doctors some slack to try new ideas, or medicine would never move forward.

Likewise for pilots. They can’t really fly into an airport on a whim from any direction and land as they please. However, they do have to fly around bad weather and improvise when things go wrong. Yet they these things from a culture that has deep underlying concerns about safety, working within defined rules, for the very good reason that hundreds of lives and millions of dollars-worth of aircraft are at stake.

A safety-first culture is vital for passengers. However, if it pervades every part of an airline, hospital or government department, it makes innovation problemmatic, particularly when a “disruptive” idea comes along. Think about low-cost airlines: their traditional rivals the world over have had a hard time adapting because “it’s not the way we do things round here.” So the culture of big organizations is to create frameworks that contain the messiness of innovation, constraining it in the process.

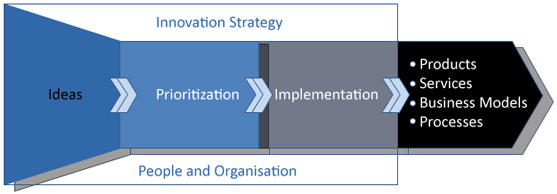

This is one of the most popular frameworks. All the mad ideas are safely held in a box on the left. Wise people choose the best ones, then a team gets cracking to turn them into something that the public can buy on the right. In theory.

In practice, a huge amount of effort goes into developing ideas that never get taken anywhere, the selection process doesn’t really take into account the needs of the market and, during implementation, it’s all too easy for well-intentioned “bells and whistles” to get added on even if they are not what customers want.

Nevertheless, it looks suitably thrusting – like a rocket on its side. Indeed this kind of framework is exactly what you need to do something like getting to the moon. When President JF Kennedy set NASA the challenge:

… before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.

He wanted it done in an orderly way. He wanted results because he was footing the bill:

No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

Heads of state had not always been so prescriptive.

Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He (Cheng Ho) was sent on seven voyages by the Ming emperor, in command of a fleet comprising more than 200 ships. The crews knew how to sail and their Admiral had a general brief to create benefits for China. But he didn’t have instructions to achieve a specific goal most of the time.

Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He (Cheng Ho) was sent on seven voyages by the Ming emperor, in command of a fleet comprising more than 200 ships. The crews knew how to sail and their Admiral had a general brief to create benefits for China. But he didn’t have instructions to achieve a specific goal most of the time.

Zheng He was in command of day-to-day operations at any moment and he made up goals as he went along. He was like my son Max playing with Lego, not sure if he would end up creating a rocket or a dinosaur. His job was to be creative, using his skill and experience to get the best possible result.

Saras Sarasvathy has studied successful entrepreneurs. She’s found that they think and act much more like Zheng He than the NASA engineers behind the Apollo missions. In other words, entrepreneurship is about the journey more than it’s about a specific destination.

Sarasvathy’s findings resonate with the recommendations of Lean Innovation pioneers like Steve Blank and Eric Ries. They promote a model of innovation that is very close to Kolb’s learning cycle. It’s exactly what we practice at JFDI.Asia and it comes with a cost. We have to accept at the start that we can’t know where we are going to end up.

Unlike the rocket-shaped innovation framework that tracks a trajectory towards a definite destination, lean innovation only offers a journey that will take you to somewhere good. That can be very challenging in large organizations. It’s a key reason why many of the truly original ideas in business are now coming from small start-ups that have no reason to feel threatened by something new. For dinosaurs in business, it’s very different.

Unlike the rocket-shaped innovation framework that tracks a trajectory towards a definite destination, lean innovation only offers a journey that will take you to somewhere good. That can be very challenging in large organizations. It’s a key reason why many of the truly original ideas in business are now coming from small start-ups that have no reason to feel threatened by something new. For dinosaurs in business, it’s very different.

Take Kodak. For years, their technology was sold on the basis that film would capture “Kodak Moments – rare, one-time moments captured with a photo.” Now the phrase “Kodak Moment” has taken on a new meaning. It’s the moment when a company that’s held a dominant position for years suddenly realizes that it’s become irrelevant as its core product is being undermined by a new technology. For Kodak, that technology was digital imaging. For traditional telecommunications companies, it’s Voice-over-IP like Skype.

Joi Ito is a successful entrepreneur, investor and Director of the MIT Media Lab. He describes the new way of working like this in a recent article about Innovation On The Edges:

In the old days, you’d have to have an idea and then you’d write a proposal for a grant or a VC, and then you’d raise the money, you’d plan the thing, you would hire the people and build it. Today, what you do is you build the thing, you raise the money and then you figure out the plan and then you figure out the business model. It’s completely the opposite, you don’t have to ask permission to innovate anymore.

In other words, there’s a political dimension to innovation. It involves change and it involves risk, things that may not feel comfortable in an orderly society like Singapore. Yet, as the country’s Prime Minister said last week in New Delhi, it’s a price that has to be paid:

There are some areas where you must accept that you cannot do things in a linear or hierarchical way. I decide, you refine, he implements. You have to have an interaction, discussion. There will be objections, you have views but something has to be done.

There are some areas where you must accept that you cannot do things in a linear or hierarchical way. I decide, you refine, he implements. You have to have an interaction, discussion. There will be objections, you have views but something has to be done.

With the support of South East Asia’s start-up community, SingTel, SPRING Singapore and the MDA, JFDI has proved that the lean innovation process behind US internet innovations like Dropbox and Airbnb can work in Asia too. It will be fascinating to see how many other organizations locally pick up the same approach and adapt it to drive innovation too.

We’re committed to sharing what we have learned, disclosing what doesn’t work as well as what does and we welcome a discussion with anyone who’s interested to give the lean approach to innovation a go. If your organization would like to explore how Lean Innovation could open up new possibilities, please contact us.

This is the final part of a three-part series looking at the links between creativity and lean innovation.